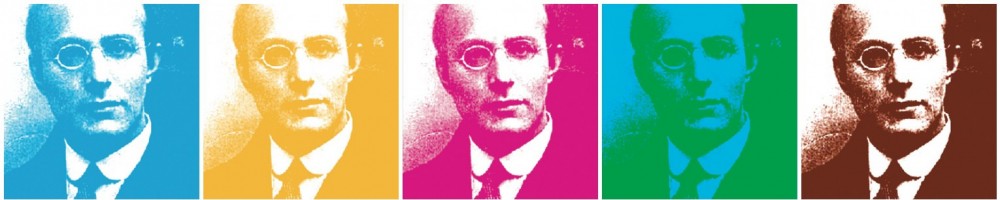

Écrit par Keith Hart

Autrement dit : la monnaie est toujours sociale, globale et virtuelle…

Cette conférence a été prononcée dans le cadre de la troisième rencontre de l’Université populaire et citoyenne du CNAM, « L’argent autrement : la monnaie peut-elle être sociale ? La finance peut-elle être solidaire ?, le 13 octobre 2007.

Summary

The term « social money » suggests that some money, such as the form we are familiar with, is not social, even anti-social. With Mauss, I consider that money’s principal function, like that of the gift, is the extension of society, just as Simmel saw society’s potential for universality reflected in money. People have always made money personal and social by adapting it to their own special purposes, but this was in dialectical tension with its ability to reach the most inclusive levels of association. It is therefore mistaken for proponents of « Local Exchange Systems » (SEL) to imagine that the principles they wish to introduce are something new; and, by designing money as a closed local circuit, they have failed to harness money’s global potential. Too often, in unconscious mimicry of national currencies, these introverted initiatives stand alone and fail as a result. The movement to reform money needs to embrace the power of federation more wholeheartedly in future. This in turn requires us to engage with the virtual society opened up by the internet. Money’s ability to make social connection has been vastly expanded by the « network and networks » and those who wish to work for economic democracy cannot afford to turn their backs on these developments. Michael Linton, who founded LETS 25 years ago, is now pioneering this next phase — developing smart-card technology, new software and multiple domain naming systems as the means of sustaining money on an open source basis.

The text

When Bronislaw Malinowki published Argonauts of the Western Pacific in 1922, he revealed a world economy in microcosm. No island was self-sufficient, but each depended on a complex overseas trade organized without markets and money, capitalists or states. Rather, big men and chiefs provided the peace for the trade by giving each other valuables (known as kula). Their ethos was one of ceremony, altruism and generosity. Homo economicus was restricted to individual barter between the lowly followers of these aristocrats. Malinowski insisted that the valuables were not currency since they were not an impersonal medium of exchange or standard of value. He was not alone in promoting the values of a past era. Socialists had long advocated a return to non-market economy. Even bourgeois ideology sometimes imagined a time of primitive communism which had been replaced by our own regrettably selfish but more efficient economy.

Marcel Mauss drew the opposite conclusion when comparing the archaic gift with contemporary western economy. We tend to emphasize how problematic it is to be both self-interested and mutual; yet the two are often inseparable in practice. Mauss held that human institutions everywhere are founded on the unity of individual and society, freedom and obligation, self-interest and concern for others. The pure types of selfish and generous economic action obscure the complex interplay between our individuality and belonging to others in subtle ways. Rather than oppose gift and market, he preferred to see them both as instances of a universal human propensity for exchange. Markets and money are necessary for the extension of human society, but their contemporary impersonal form is unsustainable. The kula valuables might well be considered a form of personal money. Capitalist institutions too combine self-interest and elements of the gift; and sociologists should make this more visible, while rejecting the one-sided accounts generated by capitalism’s apologists and detractors alike.

To speak of ‘social money’, therefore, suggests that some money, such as the form we are familiar with, is not social, even anti-social. It may be that the word ‘capitalism’ has become too familiar and general for specific analytical purposes, but it certainly evokes both the economic inequality and the innovation that are endemic to our world. In The Memory Bank (2000), I tried to separate the idea of ‘markets’ and ‘money’ from their association with ‘capitalism’. With Mauss, I consider that money’s principal function, like that of the gift, is the extension of society, just as Simmel saw society’s potential for universality reflected in money. As sociologists like Zelizer (1994) have shown, people have always made money personal by adapting it to their own special purposes. It is almost a cliché of anthropology and history that money is usually subordinated to social ends in non-capitalist economies (Parry and Bloch 1989). When money and markets are understood exclusively through impersonal models, awareness of this neglected dimension is surely significant. But the economy exists at more inclusive levels than the person, the family or local groups. This is made possible by money and markets in their more abstract dimensions; and the economists remain unchallenged there. It will not do to replace one pole of a dialectical pair with the other.

When Michael Linton invented LETS in British Columbia a quarter-century ago, he had in mind Let’s go! Let’s do it! rather than passively allowing the money shortage of a recession to keep people unemployed. But, when pressed for its meaning as an acronym, he allowed that it might be understood as ‘Local Exchange Trading System’ and this meaning has been taken up in France where « Systèmes d’échange locale » (SEL) evoke an ancient salt currency. It has become conventional that to design money as a closed circuit means restricting participation to the local level. This goes along with a reification of society as face-to-face relations, even though anthropologists have long known that small-scale societies (such as families or villages) often sustain the most intractable conflicts. Consistent with this emphasis, local exchange systems have often become introspective clubs where an active few alienate the many with their endless manoeuvring for control. Most of these systems choose to stand alone in unconscious mimicry of the national currencies they claim to oppose; and the failure rate is high. The movement to reform money needs to embrace the power of federation more wholeheartedly in future.

The classical economists focused on the commodity’s higher-order ability to enter into abstract relations of exchange with other commodities through money (quantity) rather than on its concrete value in use (quality). But the commodity remains something useful and in that use lies its concrete realization. The reality of markets is not just universal abstraction, but this mutual determination of the abstract and the concrete. If you have some money, there is almost no limit to what you can do with it, but, as soon as you buy something, the act of payment lends concrete finality to your choice. Money’s significance thus lies in the synthesis it promotes of impersonal abstraction and personal meaning, objectification and subjectivity, analytical reason and synthetic narrative. Its social power comes from the fluency of its mediation between infinite potential and finite determination. It is not enough to retreat into the local; we urgently need to develop more effective institutions at the level of world society too. Money’s ability to sustain local meaning and universal connection at the same time is an indispensable means to that end. Local money without global pretensions is as sexy as kissing your sister.

If money is global as well as social, we must also recognize that it is virtual. Keynes (1930) distinguished between its abstract function as ‘money-of account’ and the thing that passes between hands, ‘money proper’. Identification of currency with precious metals – either as coinage or later as the gold standard – lent credence to the idea of money as a scarce natural resource, obscuring its more fundamental role simply as a measure. We may lack the raw materials to build a house, but we can never be short of the metres, kilos and litres to measure the wood, cement and paint. So too it is with money; and this has become more evident as transactions have become increasingly virtual. The society opened up by the digital revolution now offers universal means for the expression of universal ideas. Money’s ability to make social connection has been greatly amplified by the internet, « the network and networks », so that markets, world society and virtual reality feed each other’s explosive growth at this time.

Those who wish to work for economic democracy cannot afford to turn their backs on these developments. Yet many of them are unfortunately wedded to reactionary ideologies that owe more to Aristotle and the medieval schoolmen than to contemporary social possibilities. Linton has always regretted the narrow localism that has plagued the movement for ‘social money’ in its first two decades. He is working with a number of colleagues (http://openmoney.info) to pioneer the next phase — developing smart-card technology, new software and multiple domain naming systems as the means of sustaining money on an open source basis. Some of the principles remain the same – the design of money as a closed circuit, the money issued by each participant as a promise to contribute their own goods and services – but others, such as sophisticated communication between circuits, are new. Now individuals may join any number of these circuits at once, reflecting their interests at several levels, not just the local, with a single smart card able to support simultaneously 15 or more of the circuits. It is lonely work and there is still much to be done; but without it ‘social money’ will remain an irrelevance to a world moving rapidly in a different direction.

Keith Hart, professor of Anthropology, Goldsmiths University of London